Follow-up Rounds

5/26/2017

Article inspired by: Dr. Jeremy Price, PGY-3

THE CASE

3 month old female BIBEMS for poor feeding x 2 days as per the mother. One week ago, the mother noticed patient occasionally falls asleep while feeding. On ROS, mom has noticed occasionally increased work of breathing. Over last 12 hours, patient drank 1 ounce of formula 6 hours ago and is refusing breast feeding. Mom endorses normal wet diapers/stools and denies any fevers, vomiting or diarrhea.

Physical Exam:

Triage Vitals: HR: 158, RR: 60, SpO2: 100%, Temp: 99.5F (rectal), Weight: 6.3kg (50% percentile)

- General: NAD, Well-appearing infant, Smiling at provider

- HEENT: NC/AT, Anterior fontanelle open and flat, Posterior oropharynx wnl

- Chest: CTA bilaterally, No wheezing/rales

- Cardiovascular: RRR, No murmurs/rubs/gallops

- Abdomen: Soft, NT/ND, No palpable masses, No organomegaly

- GU: Normal female genitalia

- Skin: Intact, no rashes

- Neuro: Alert, Awake, Symmetric face, Normal tone

Critical Intervention:

-Baby appeared well and was observed during a feed before deciding disposition.

-During the feed, patient appeared diaphoretic and only took 1 ounce before refusing any more formula.

-After the feed, patient noted to be tachypneic in 60s-70s, with retractions

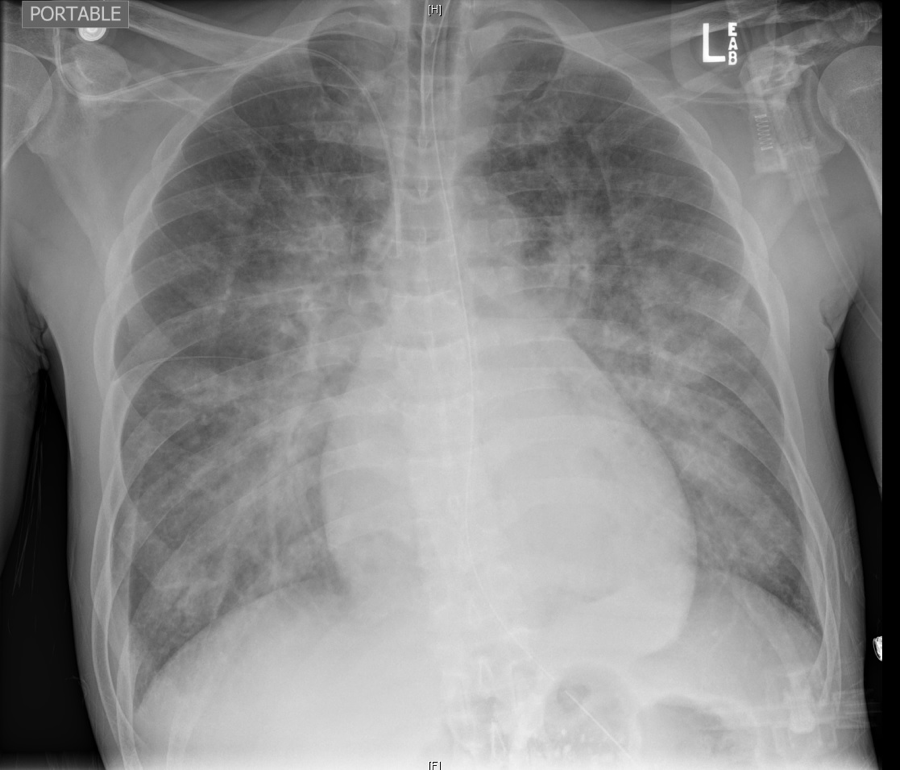

CXR Interpretation:

Markedly enlarged cardiac silhouette. The lungs are enlarged and the vascularity is increased

Follow-Up Studies:

- TTE: showing severely dilated LV with EF 13%, Rest of heart structurally normal, with normal coronary origins, no coarctation of aorta

- Pro-BNP: 73,926

- Troponin: 0.35

THE TALK

The presentation of pediatric heart failure varies drastically based on its cause and is different from the classic presentation of heart failure we are used to in the adult population.

What are some signs I should look for on my physical exam to suspect heart failure?

- Tachycardia

- Decreased perfusion (cool/mottled extremities, decreased capillary refill, low BP)

- S3 gallop

- Respiratory distress (tachypnea, retractions, grunting)

- Systemic congestion (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, peripheral edema)

- High BP in upper extremities (suggestive of coarctation of aorta)

- Weak pulses in lower extremities (suggestive of coarctation of aorta)

- Palpable “thrill” (suggestive of a shunt lesion)

- “Heave” or laterally displaced point of maximal pulse (suggestive of long-standing cardiomyopathy)

Is there any system I can use to classify heart failure similar to the NYHA classification in adults?

Modified Ross Heart Failure Classification

- Class I: No limitations or symptoms

- Class II:

- Infants: Mild tachypnea or diaphoresis with feeding

- Older children: Mild to moderate dyspnea on exertion

- Class III:

- Infants: Growth failure and marked tachypnea or diaphoresis with feeding

- Order children: Marked dyspnea on exertion

- Class IV: Symptoms as rest (tachypnea, retractions, grunting or diaphoresis)

Okay, what tests can I order to confirm my diagnosis?

- CXR (to assess for cardiomegaly and pulmonary congestion)

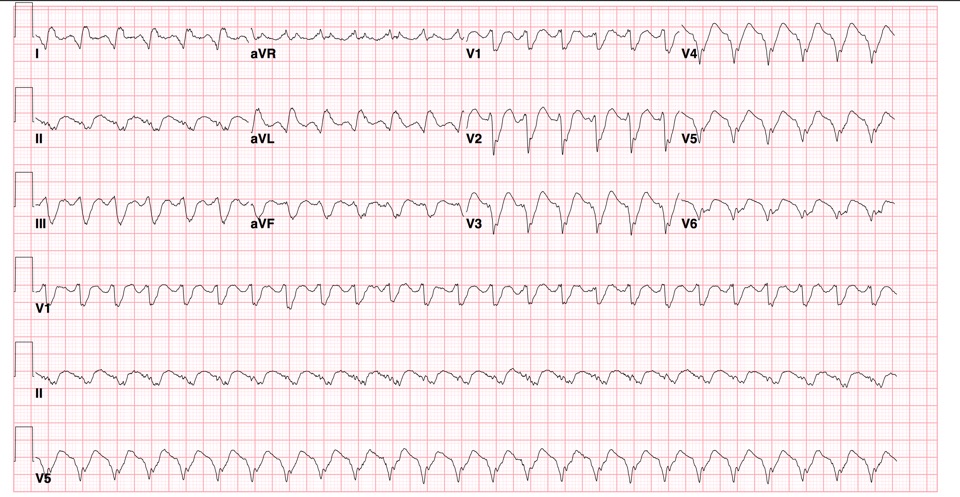

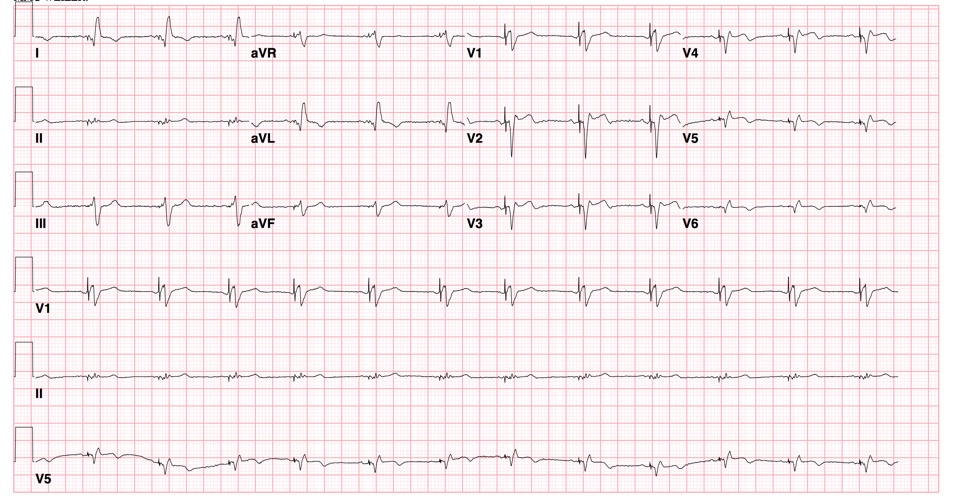

- EKG (ST segment and T wave abnormalities are common in cardiomyopathy)

- Echocardiogram (to assess anatomy, ventricular size and function)

- Lab Tests

- Chem, including LFTs

- CBC (to r/o anemia as an exacerbating factor)

- Pro-BNP

- Troponin

This was too long and I didn’t read it- what should I know?

- If you have a pediatric patient with a feeding complaint who looks amazing in your ED, watch the patient during a feed to see what the patients are talking about!

REFERENCES/FURTHER READING:

- Singh, Rakesh K., and TP Singh. “Heart Failure in Children: Etiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis.” UpToDate. 21 Apr. 2017. Web.

- Singh, Rakesh K., and TP Singh. “Heart failure in children: Management.” UpToDate. 21 Apr. 2017. Web.

- Jayaprasad, N. “Heart Failure in Children.” Heart Views : The Official Journal of the Gulf Heart Association. Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd, Sept. 2016. Web.