Follow-up Rounds

1/13/2017

Article inspired by: Dr. Maninder Singh, PGY-3

THE CASE

37 y/o M with no significant PMHx who p/w “allergic reaction” after taking the first dose of PCN 2 hours ago prescribed for Strep Throat diagnosed at an urgent care center. He endorses a sore throat and fever x 2 days but denies any hives or lip/tongue swelling. Denies any prior allergic reactions.

Physical Exam:

- Vitals: BP: 133/76, HR: 107, RR: 15, Temp: 99F, SpO2: 100%

- General: Appears well

- HEENT: NC/AT, PERRL, EOMI, Uvula is midline, Moist mucous membranes, No tonsillar abscesses, Muffled voice, No visible upper oral airway obstruction, Increased saliva production noted; Neck supple, Some lymph node swelling to left precervical nodes

- Cardiovascular: RRR, No murmurs/rubs/gallops

- Chest: CTA b/l, No wheezes/rales/rhonchi

- Abdominal: Soft, NT/ND, BS+ x4

- Extremities: FROM

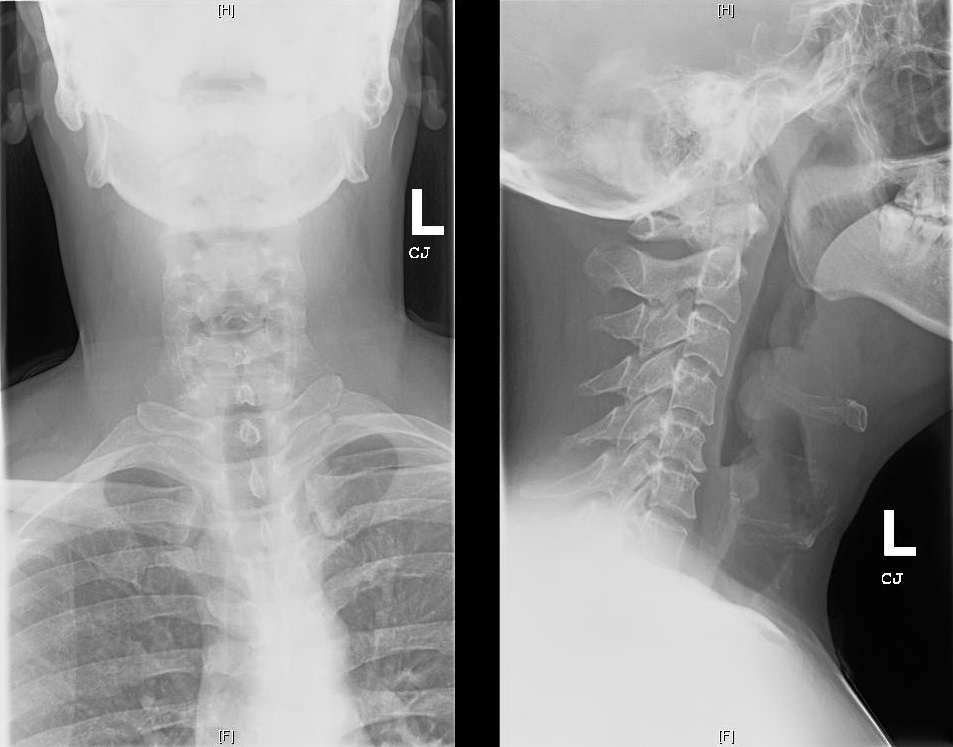

Soft Tissue Neck X-ray:

THE TALK

What is an epiglottis?

- Back wall of the vallecular space below base of tongue

- Infectious epiglottitis = cellulitis of epiglottis

- Progresses to involve entire supraglottic larynx (including aryepiglottic folds and arytenoids) leading to difficulty breathing

Isn’t epiglottitis a pediatric diagnosis?

- Incidence decreased in children since haemophilus influenza vaccination

- Incidence in adults (2006): 1.6 cases per 100,000 adults

- Usually a/w HTN, DM, Substance abuse or immune deficiency

How do I diagnose it?

- Fiberoptic nasal laryngoscopy = gold standard

- Lateral neck x-ray: look for the “thumbprint” sign

- CT neck (if diagnosis unclear)

What do I do if I suspect/diagnose it?

- MANAGE AIRWAY- Be prepared for a cricothyrotomy!

- Have patient sitting up in bed

- Consider prophylactic intubation

- Risk of laryngospasm with scope

- Heliox (mixture of Helium and Oxygen) can be used as a temporizing measure

- Augmentin or Ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn) are preferred initial antibiotics

- Consider Vancomycin if patient is critically ill and MRSA a possible etiology

- NSAIDS for pain control

- +/- Steroids for symptomatic relief

This was too long and I didn’t read it- what should I know?

- Patient with sore throat and muffled voice but no obvious signs of upper airway obstruction need further work up

- Have your triple set up ready (direct laryngoscope, video laryngoscope and cricothyroidectomy) and have backup (ENT/Anesthesia) available for a difficult airway

REFERENCES/FURTHER READING:

- Frantz TD, Rasgon BM, Quesenberry CP. Acute Epiglottitis in Adults: Analysis of 129 Cases. 1994;272(17):1358-1360.

- Woods, Charles. “Epiglottitis (supraglottitis): Clinical Features and Diagnosis.” UpToDate, 23 June 2015. Web.

- Rogers, Matt. “Epiglottitis.” Core EM, 26 Aug. 2015. Web.